Have you ever felt frustrated when learning a new skill, wondering if you’ll ever make progress? You’re not alone. Barbara Oakley, now a renowned professor and learning expert, once struggled intensely with math. During her early education, Oakley found mathematics difficult and discouraging. However, her story took an inspiring turn. After serving in the military, she made a bold decision to confront her weaknesses head-on by enrolling in engineering courses. Through sheer persistence and by developing effective learning strategies, Oakley not only overcame her initial difficulties but went on to earn a Ph.D. in systems engineering. Today, she’s a prominent advocate for learning how to learn, co-teaching the popular online course “Learning How to Learn” on Coursera. Oakley’s journey is a powerful reminder that staying motivated when learning feels frustratingly slow can lead to remarkable transformations.

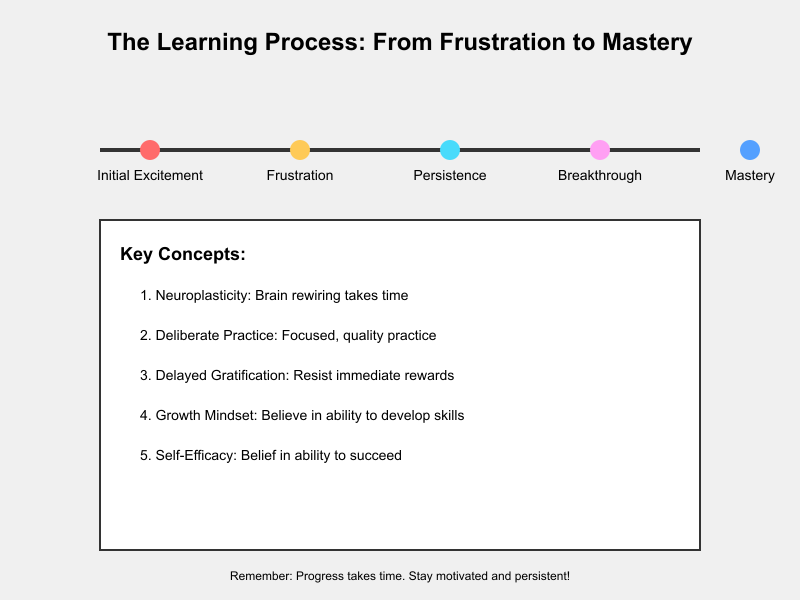

Learning is a journey, not a sprint. It’s about embracing the process, understanding the science behind skill acquisition, and developing strategies to stay motivated when progress seems slow. Let’s explore how you can master the art of learning, even when it feels frustratingly slow and immediate results are hard to come by.

Neuroplasticity and The Hidden Mechanics of Learning

Your brain is constantly rewiring itself as you learn. This process, known as neuroplasticity, takes time. It’s like building a house – you need to lay a strong foundation before you see the walls going up.

Neuroscientists have discovered that learning involves the creation and strengthening of neural connections. When you practice a new skill, neurons in your brain fire together, forming new pathways. The more you practice, the stronger these pathways become. This is why consistent practice over time is crucial for mastery, even when the lack of visible progress feels frustrating.

Dr. Anders Ericsson, a pioneer in the study of expert performance, emphasizes the importance of deliberate practice. This isn’t just about putting in hours; it’s about focused, quality practice that pushes you just beyond your current abilities. Ericsson’s research shows that experts in various fields, from musicians to athletes, engage in this type of practice regularly, staying motivated despite the slow pace of improvement.

Deliberate practice involves:

- Setting specific goals for each practice session

- Focusing intently on improving particular aspects of your performance

- Seeking immediate feedback

- Constantly pushing yourself out of your comfort zone

It’s important to note that this process is often uncomfortable and can lead to frustration. You might feel like you’re not making progress, but in reality, your brain is working hard to build those neural pathways. This is why patience and persistence are key components of effective learning.

Another fascinating aspect of learning mechanics is the role of sleep. During sleep, especially in the deep stages, your brain consolidates new information and skills learned during the day. This process, known as memory consolidation, is crucial for long-term learning. So, when you’re learning something new and feeling frustrated, make sure you’re getting enough quality sleep!

The Psychology of Delayed Gratification

Our brains are wired for quick rewards. When we achieve something, our brain releases dopamine, making us feel good. But learning often requires delayed gratification – the ability to resist immediate rewards for long-term benefits. This delay can be a source of frustration for many learners.

Walter Mischel’s famous “marshmallow experiment” in the 1960s and 70s beautifully illustrated this concept. In this study, children were given a choice: eat one marshmallow now, or wait 15 minutes and get two marshmallows. The researchers then followed these children into adulthood. Surprisingly, they found that those who were able to delay gratification as children tended to have better life outcomes, including higher SAT scores and lower body mass index.

This ability to delay gratification is crucial in learning. When you start learning a new skill, progress is often slow and not immediately visible. This can be frustrating, leading many people to give up. However, those who can push through this initial phase of apparent lack of progress often reap significant rewards later.

The psychology behind delayed gratification involves several key factors:

- Future Orientation: People who are better at delaying gratification tend to have a stronger future orientation. They can vividly imagine and connect with their future selves, making it easier to make decisions that benefit that future self.

- Emotional Regulation: The ability to manage emotions, especially frustration and impatience, is crucial for delayed gratification. Techniques like mindfulness and cognitive reframing can help in this regard.

- Attention Control: Being able to direct your attention away from immediate temptations and towards your long-term goals is a key skill in delayed gratification.

- Trust in Future Rewards: Believing that the promised future reward will actually materialize is important. In learning, this translates to having faith that your efforts will eventually pay off, even when progress feels frustratingly slow.

Interestingly, research has shown that the ability to delay gratification isn’t just an innate trait – it can be developed and strengthened over time. This is great news for learners, as it means we can train ourselves to become more patient and persistent in our learning journeys, even in the face of frustration.

One effective strategy for improving delayed gratification is to create a system of small, immediate rewards for progress towards your larger goal. For instance, you might treat yourself to a favorite snack after completing a challenging study session. This helps bridge the gap between the immediate desire for reward and the long-term benefits of learning, helping you stay motivated when learning feels slow.

Understanding these psychological principles can help you stay motivated when learning seems tough. Remember, the ability to delay gratification is like a muscle – the more you exercise it, the stronger it becomes.

Strategies to Keep You Going

- Set Micro-Goals Break down your learning journey into small, achievable goals. Celebrate these wins to keep your motivation high.

- Embrace the Growth Mindset Adopt what psychologist Carol Dweck calls a “growth mindset.” Believe that your abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work.

- Focus on the Process Instead of fixating on results, enjoy the learning process itself. Each practice session is a step forward, even if it doesn’t feel like it.

- Keep a Learning Journal Document your progress. On days when you feel stuck, look back to see how far you’ve come.

- Seek Constructive Feedback Regular feedback can highlight improvements you might have missed and guide your future efforts.

- Practice Mindfulness Mindfulness techniques can help manage frustration and keep you focused on your long-term goals.

- Stay Physically Active Regular exercise boosts cognitive function and overall well-being, supporting your learning efforts.

- Connect with Fellow Learners Join a community of learners. Shared experiences can provide encouragement and valuable insights.

- Visualize Success Imagine yourself having mastered the skill. This mental rehearsal can boost motivation and confidence.

The Power of Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy – your belief in your ability to succeed – plays a crucial role in learning. Psychologist Albert Bandura, who pioneered the concept, found that individuals with high self-efficacy are more likely to persist in the face of challenges, put forth greater effort, and ultimately achieve higher levels of success.

But what exactly is self-efficacy, and how does it differ from concepts like self-esteem or confidence? While self-esteem refers to your overall sense of self-worth, and confidence is a general feeling of trust in your abilities, self-efficacy is more specific. It’s your belief in your capacity to execute behaviors necessary to produce specific performance attainments. In other words, it’s your conviction that you can successfully perform a particular task or master a specific skill.

Bandura identified four main sources of self-efficacy:

- Mastery Experiences: This is the most influential source of self-efficacy. When you successfully perform a task, you build a robust belief in your ability to succeed. Each success builds upon the last, strengthening your self-efficacy.

- Vicarious Experiences: Seeing people similar to yourself succeed by sustained effort raises your beliefs that you too possess the capabilities to master comparable activities. This is why role models and mentors can be so powerful in the learning process.

- Social Persuasion: Verbal encouragement from others helps people overcome self-doubt and instead focus on giving their best effort to the task at hand. Receiving positive feedback and encouragement can boost your belief in your abilities.

- Emotional and Physiological States: Your mood, emotional state, physical reactions, and stress levels can all impact how you feel about your personal abilities in a particular situation. Learning to minimize stress and elevate mood when facing difficult or challenging tasks can improve your sense of self-efficacy.

The beauty of self-efficacy is that it’s not a fixed trait – it can be developed and strengthened over time. Here are some strategies to build your self-efficacy:

- Set Yourself Up for Success: Start with small, achievable goals. As you accomplish these, your belief in your ability to succeed will grow. Gradually increase the difficulty of your goals as your self-efficacy strengthens.

- Celebrate Your Wins: Take time to acknowledge and celebrate your successes, no matter how small. This reinforces the connection between your efforts and positive outcomes.

- Learn from Others: Seek out people who have succeeded in areas where you want to improve. Observe their strategies and behaviors, and try to apply these in your own life.

- Seek Constructive Feedback: Regular, specific feedback can help you identify areas of improvement and recognize progress you might have overlooked. This can come from teachers, mentors, peers, or even self-reflection.

- Reframe Negative Self-Talk: Be aware of your inner dialogue. If you catch yourself thinking “I can’t do this,” try reframing it to “I can’t do this yet, but I’m learning and improving.”

- Visualize Success: Imagine yourself successfully performing the task or skill you’re trying to master. This mental rehearsal can boost your belief in your ability to succeed when you actually perform the task.

- Practice Self-Care: Take care of your physical and emotional well-being. Regular exercise, adequate sleep, and stress-management techniques can all contribute to a more positive physiological state, which in turn can boost your self-efficacy.

Remember, building self-efficacy is a gradual process. It’s normal to face setbacks and moments of doubt. The key is to persist, learn from your experiences, and maintain a growth-oriented mindset.

In the context of learning, high self-efficacy can lead to greater engagement with the material, increased effort and persistence in the face of challenges, and ultimately, better learning outcomes. When you believe in your ability to learn and master new skills, you’re more likely to approach learning opportunities with enthusiasm rather than anxiety or avoidance.

As you continue on your learning journey, pay attention to your self-efficacy. Notice how it fluctuates and what influences it. By actively working to build and maintain a strong sense of self-efficacy, you’ll be better equipped to handle the challenges of learning and more likely to achieve your learning goals.

Putting It All Together

Remember Barbara Oakley, the math-averse student who became an engineering professor? She applied many of these strategies throughout her learning journey. Despite initial frustrations with mathematics, Oakley persisted and transformed her abilities. Her success wasn’t just about the engineering skills she developed, but also about the growth in her self-efficacy. Each small win, from grasping a challenging concept to solving complex equations, built her belief in her ability to learn and master difficult subjects.

Oakley’s journey exemplifies how understanding the science of learning, embracing delayed gratification, implementing effective strategies, and building self-efficacy can help maintain motivation and achieve learning goals. She went from struggling with basic math to earning a Ph.D. in systems engineering and becoming a leading voice in the field of learning how to learn.

Learning without immediate results is challenging, but it’s also an opportunity for growth. By applying the principles we’ve discussed – from understanding the neuroscience of learning to practicing delayed gratification and building self-efficacy – you can navigate the frustrations of slow progress and achieve your learning goals.

Are you ready to transform your learning journey? Start by choosing one strategy from this article and implement it today. Remember, every expert was once a beginner. Your perseverance today is laying the foundation for your future success, just as it did for Barbara Oakley.

What new skill will you commit to learning, knowing that progress may feel frustratingly slow at times? And how will you build your self-efficacy along the way? Like Oakley, you might find that the subjects you once struggled with could become the areas where you develop the greatest expertise.

References

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman and Company.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363-406.

Mischel, W., Ebbesen, E. B., & Raskoff Zeiss, A. (1972). Cognitive and attentional mechanisms in delay of gratification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 21(2), 204-218.

Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., & Rodriguez, M. I. (1989). Delay of gratification in children. Science, 244(4907), 933-938.

Stickgold, R. (2005). Sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Nature, 437(7063), 1272-1278.

Walker, M. P., & Stickgold, R. (2004). Sleep-dependent learning and memory consolidation. Neuron, 44(1), 121-133.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 82-91.